Screening

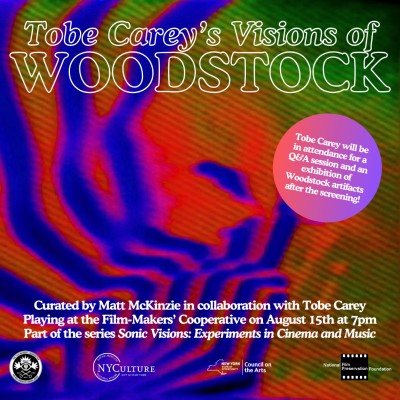

Join us at the Film-Makers' Cooperative on Thursday, August 15th, at 7pm, for a program of films and video art by longtime FMC member Tobe Carey, chronicling the music scenes and countercultural communities of Woodstock, New York, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Curated by Matt McKinzie in collaboration with Tobe Carey.

*$10 SUGGESTED DONATION*

Program:

- Banjo Feedback, 1974, video-to16mm, color, sound, 13 minutes

- A True Light Beaver Film: After the Revolution, 1970, 16mm, color, sound, 13 minutes

- Family Astrology, 1970, 16mm-to-digital, color, sound, 34 minutes

- The True Story of Set Your Chickens Free, 1977, video-to-digital, color, sound, 10 minutes

Total Run Time: 70 minutes.

Program note by Matt McKinzie:

From August 15th to 18th, 1969, Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in Bethel, New York became the epicenter of the proliferating hippie counterculture — and a culmination of the rock music scene that both propelled (and was propelled by) that counterculture — with the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as “Woodstock.” Jimi Hendrix desecrated the Star Spangled Banner, Melanie Safka saw candles in the rain and became a household name, and miles away in a hotel room with record executive David Geffen, Joni Mitchell (who was scheduled to perform at the festival but urged by Geffen to back out at the last minute to appear on the Dick Cavett Show) watched the proceedings on television. From that vantage point, she wrote “Woodstock”: the iconic song that, in the words of David Crosby, “captured the feeling and importance of the festival better than anyone who had actually been there.”

Mitchell’s lyrics — particularly the Edenic refrain “we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden” — were at the forefront of my mind as I watched Tobe Carey’s films documenting hippie life, music, family, and community in Woodstock, New York, in the late 1960s and 1970s. While Yasgur’s farm was in fact located 40 miles southwest of Woodstock, the watershed musical event that occurred there was named after the town that inspired it, where Carey and other members of his commune, the True Light Beavers, settled in June 1969 — a mere two months before the festival in Bethel. There, Carey and his community remained for decades, as delineated in the July 1994 New York Times feature by Jacques Steinberg: Woodstock Nation, and Address: Social Conscience and Freedom Shine for Those Who Stayed. That article, published a month prior to the 25th anniversary Woodstock festival, noted:

Unlike countless other members of the broader Woodstock generation, this town’s aging hippies have stopped far short of selling out. Those who have stayed in Woodstock — when places like New York City beckoned with promises of wealth and status — say they remained because they relished the simple quality of life, the emphasis on individual freedom and the unspoiled surroundings. (Mr. Carey, for example, lives and works in a modest A-frame house with deep woods on all sides.) And recent interviews with Mr. Carey, Ms. Jamison and eight others who settled in the Woodstock area in the late 60’s and early 70’s make clear that their social consciousness still burns bright, even if they are now more likely to stage a protest by sending an E-mail message to a congressman than picketing his office.

Watching Carey’s films induced a feeling of euphoria; admittedly, as a lover of most everything that came out of ‘60s/‘70s hippiedom, I am a biased viewer. As a member of Generation Z, moreover, I tend to regard those countercultural years with the mix of romanticism and naïveté felt by anyone who hasn’t actually lived through a specific historical period. No doubt it wasn’t all rainbows and butterflies, but Carey’s films crystallize, for me, what it must have really looked, felt, and sounded like to get “back to the garden,” as Mitchell’s sun-dappled soprano (not yet rained-out by the Blue years) so ethereally crooned. It’s also worth noting that Carey documented (in incisive and witty fashion) the days leading up to the 25th anniversary Woodstock festival in the documentary Woodstock ‘94: Not the Music… Just the Scene, which saw the anti-establishment and anticapitalist iconography of the original fest co-opted by major corporations (e.g. MTV, Pepsi) eager to cash in on the event. On several occasions, Carey’s interviewees — many of whom attended the 1969 event in Bethel — are heard speaking or singing the lyrics of Mitchell’s song; sometimes earnestly, though often (considering the circumstances) with a mix of irony and melancholy.

The titles in this program span from 1970 to 1977 and capture the halcyon (and at times remote) bliss of those “garden” years in Woodstock in the decade following the eponymous festival. Well-known artists like Hendrix, Safka, and Mitchell may initially come to mind at the mention of the “Woodstock” moniker, though Carey’s films subvert these knee-jerk celebrity associations by situating the musical and countercultural milieu typically linked to the 1969 Bethel event in the sylvan intimacy of the blue-collar town that proved its namesake. This intimacy centers lesser-known and local artists in Carey’s work. For instance, banjoist Billy Faier (who spent much of his adult life in Woodstock, rubbed shoulders with temporary Woodstock resident Bob Dylan, and transcribed music for Pete Seeger in the early ‘60s) performs two original tunes in Banjo Feedback (1974). This hallucinogenic black-and-white video was colorized with a Siegel Colorizer (developed in 1968 by video pioneer Eric Siegel) and completed at the Experimental Television Center with the support of the New York State Council on the Arts and Woodstock Community Video. Ingeniously, Carey’s analog video feedback is triggered by Faier’s finger-picking, making Banjo Feedback a collaborative effort that finds kinship with the exploratory and often playful early video work of fellow pioneers of the medium, Jud Yalkut and Bill Creston, both of whom are also represented in the collection of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative. (It’s worth noting that, in the late ‘60s, Yalkut lived about 15 minutes outside of Woodstock, in Saugerties, as part of the commune “Group 212,” though he never crossed paths with Carey). Bookending this program with Banjo Feedback is another video work made three years later, titled Set Your Chickens Free, which features a politically-charged anthem of the same name written by Curry Rinzler. Carey captures the rehearsal process and initial recording of Rinzler’s tune before documenting a rousing live performance of the song in a local tavern by the Beaverland Band, the True Light Beavers’ “house” band.

A True Light Beaver Film: After the Revolution and Family Astrology (both made in 1970) capture Carey’s family commune living, working, and playing in Woodstock’s idyllic landscape across various seasons. The former, described by Carey as a “fantasy/documentary home-movie,” begins with Carey, his then-wife Colleen, his brother Marty, and Marty’s wife Susan engaged in a meditative group exercise, at the start of which Carey notes: “we’re forming a community in the country to liberate our energies for survival.” The exercise — captured in a room painted red and adorned with candles, tomes, paintings, and artwork — is followed by sun-soaked outdoor footage of the Beavers: picnicking, swimming, playing with their children, and roaming their verdant environs in the nude with the likes of countercultural icon Abbie Hoffman and Paul Krassner of Realist magazine fame. Viewers may be unfamiliar with The Montgomeries, the band who, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, shared the Woodstock Playhouse stage with such distinguished acts as Arlo Guthrie and Geoff and Maria Muldaur, and whose serene folk-rock sound seamlessly underscores Carey’s bucolic imagery in this film. One of their closest comrades and collaborators, however, remains one of the most influential (if at times controversial) figures in rock history: Van Morrison. As remembered by The Montgomeries’ Jon Gershen:

As a founding member of this band I am in a position to tell you that during the years between 1969 (when we first moved to Woodstock), and around 1971, when he moved to California, Van and The Montgomeries were very closely linked. We had been a well known country/rock/blues band from New York City that relocated to upstate New York to work on writing material for an album our management was in the process of negotiating with Atlantic Records… This was a time when Woodstock really didn’t have any real ‘superstars’ other than Dylan… Garth Hudson used to wash his clothes at the local laundromat with us, and Richard Manuel would knock on our door at 2 in the morning when he would go off the road and get stuck in a ditch. It was very low key in those days. Van was just another recent arrival and not too many people really knew much about him. One summer evening, Van and The Montgomeries were both playing an outdoor concert at someone’s Woodstock farm and that’s how we first met. He hung out watching us play and we stayed around to see him do his thing. Needless to say, we had never heard anything like it! He was in the Astral Weeks mode at the time and it was something to witness. Anyway, the next day, he tracked us down and asked if he could come over to our place and play. Our answer was, of course! From that point on, a special bond was formed. The three pivitol [sic] members of The Montgomeries were myself; Jon Gershen, my brother David Gershen, and Tony Brown (who later went on to record Blood On The Tracks with Dylan.)

A True Light Beaver Film and its Montgomeries soundtrack perfectly complement Family Astrology, filmed the same year and featuring a similarly serene folk-rock score composed and performed by Mark Friedman (as well as an early version of “Set Your Chickens Free”). In this 34-minute film, Carey (a Cancer sun, Taurus moon, and Gemini rising) documents — through seasonal, musical, culinary, and astrological lenses — life in the snowy wilds of Woodstock with his family and other members of their commune. Not since Graham Nash wrote and recorded “Our House” has an artist so lovingly crafted a portrait of countercultural domestic bliss without making it cloying. Intermingled with Friedman’s music and Carey’s forestial footage is a candid conversation between Carey and Colleen (a Pisces sun, Scorpio moon, and Libra rising), whose remark towards the end of the film sums up Family Astrology’s aural and existential essence, and the essence of Tobe Carey’s Visions of Woodstock as a whole: “It’s really interesting to me that ever since we’ve been living together, music has been the background to our lives… whereas we just used to listen to music and dance to it, we’re making it now.”

***

The Film-Makers’ Cooperative is honored to welcome Tobe Carey to our screening room for a discussion and Q&A following this program. A number of Carey’s Woodstock artifacts will be on display, including “Feast: A Tribal Cookbook” and “Truckin’ Through Mexico with the Woodstock Community Free School,” two True Light Beaver books published by Doubleday in the 1970s. The lattermost resulted from the trip to Mexico that also begat Carey’s first feature-length documentary, “Giving Birth,” which screened at Global Village’s First Documentary Video Festival in 1975.

Tobe Carey is an independent film producer, director, and photographer. His Catskill Mountains/Hudson Valley documentaries include Luis Moses Gomez and His Mill House, The First Artist in America, Rails to the Catskills, The Catskill Mountain House and The World Around, Sweet Violets, Woodstock Summer of ’94, and Deep Water (with Robbie Dupree and the late Artie Traum). Carey’s projects also include a 20-year collaboration with performance artist Linda Mary Montano. He is the President of Willow Mixed Media, a not-for-profit arts organization devoted to creating films and videos of social concern, including work on nuclear disarmament and waste reduction, and films like Sing For the Silenced with musician Marc Black and All Politics is Local, which documents two years of political events in Woodstock and Kingston.

Program note © Matt McKinzie.

Sources:

- “American Masters: Joni Mitchell.” PBS, April 2003.

- Jacques Steinberg. “Woodstock Nation, and Address: Social Conscience and Freedom Shine for Those Who Stayed.” New York Times, 17 July 1994.

- Tobe Carey. “A True Light Beaver Film: After the Revolution” catalog entry. The Film-Makers’ Cooperative, n.d.

- “About Woodstock Playhouse.” Woodstock Playhouse, OnTheStage.Tickets, n.d.

- Jon Gershen. “Glossary entry for The Montgomeries.” Van Morrison – The Glossary, The Vanomatic Collection, 7 March 2016.